False Modesty

“Her eyebrows from a mouse’s hide,

Stuck on with art on either side,

Pulls off with care, and first displays ’em,

Then in a play-book smoothly lays ’em.”

So wrote Jonathan Swift, commemorating the 18th century’s false-eyebrow trend in his ode, A Beautiful Young Nymph Going to Bed (1731). (He goes on to describe her false teeth, hip bolsters, etc.) Though I wrote about various 18th century beauty trends in the book—wearing mouches, false beauty marks, and poufs, the gigantic towering hairstyles of the day—somehow I couldn’t work in the mouseskin brows.

In England, during the Georgian era, fashionable women wore French wigs that started far back on their heads. To accommodate the style, they shaved their real eyebrows and glued on delicately shaped mouse-skin replicas further up on their foreheads. Wearing “gently arched” brows was thought to “harmonize with the modesty of a young virgin,” tastemakers of the era reasoned. Looking wide-eyed, modest and innocent was in.

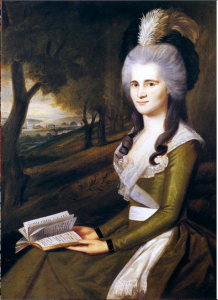

Young Ester Boardman, a society girl from New Milford, Connecticut, demonstrated the mousekin look when sitting for her portrait in the 1780s, a painting which now hangs in the American wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Ms. Jenkins, could you please provide some documentation of this? I’ve read this assertion about women in the Elizabethan era, who lost the capacity to grow brows after plucking for too many years to imitate their monarch’s pale coloring; the early Georgian era, as the result of hairlessness from using “lead-based” makeup; and now about women in the 1780s.

Swift was a satirist, not an especially reliable source for factual minutiae, and he was dead in 1745. Ester Boardman’s eyebrows don’t look especially synthetic (and there are any number of portraits of men on which their hairlines plainly reveal that they’re wearing wigs, seemingly refuting an insistence on claiming a strictly natural appearance), and neither do they reflect the appearance you claim was intended (they are both low over her eyes and nearly archless). I have also read that the use of cosmetics, wigs, etc., was far more limited in the colonies than in England, so perhaps Mistress Boardman isn’t the best examplar of this trend.

Anyway, I’d be grateful for some other evidence–thanks!

Hi, Hilary,

It’s true, documentation for the false-eyebrow trend, as with many old fashion trends, is skimpy. There are various mentions of the brows found through googlebooks, etc., though what really swayed me was that a curator for the Metropolitan Museum of Art weighed in on the feather-weight topic in this New York Times article: http://www.nytimes.com/2001/05/13/style/mirror-mirror-never-to-suffer-a-bad-eyebrow-day.html.

At the time I was searching for an image to use to illustrate the post, so it seemed a natural.

All best,

Jessica

Dear Jessica,

Thank you–that’s certainly a specific, and reputable, source!

I’m afraid it doesn’t go far in convincing me, however–a quick Google image search for Elijah Boardman showed me a man whose eyebrows varied hardly a hair from his sister’s! They are similarly strikingly dark, fairly straight, and skimming the line of the browbone. Hm!

Thanks again,

Hilary

Isn’t this the 18th century equivalent of women today, even very young women, who go through the agonies and possible drastic complications, of cosmetic surgery? It’s a phenomenon I’ve never understood–but then, I go back to the hippydippy days when au strictest naturel was considered best of all and even a touch of lipstick marked you as not a true member of the tribe.

Mouseskin eyebrows and Limerick gloves made in Limerick, Ireland, from the skin of unborn calves….Ewwwww. Beauty regime as taxidermy.