So Handy

In the 16th century, when lace trimmed handkerchiefs were the height of fashion at Queen Elizabeth‘s court, it was customary to attach one’s handkerchief to the left sleeve. Handkerchiefs, however, didn’t come into common everyday use until the 17th century—simultaneously with the rise of pockets. (I write about lace in Encyclopedia of the Exquisite, but didn’t consider the handkerchief until now.) “The lower classes wipe their noses without handkerchiefs,” one early sociologist reported, “but amonst the middle classes, it is accepted behavior to wipe one’s nose on ones’ sleeve. As for the rich, they carry handkerchiefs in their pockets.”

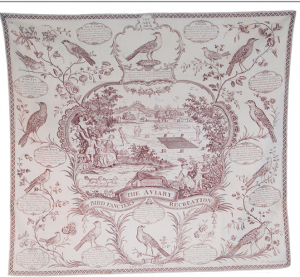

By the end of the 17th century, pedalers hawked all sorts of handkerchiefs among their wares. One traveling pedlar in the Auvergne carried 22 styles, from the simplest white cotton to those made of silk, madras or printed calico. There were those for mourning, and those for snuff. They came decorated with buttercups or spread the latest news. Handkerchiefs printed with details of the Treaty of Utrecht circulated in 1688. Another, used by the pedlars themselves, displayed a road map of England, and included a listing of the places and dates of the big country fairs. French soldiers pocketed handkerchiefs printed with horsebackriding tips or exercise routines or instructions on the proper cleaning and maintenance of their firearms.

Handkerchiefs were ever ready to blow a nose, wipe away a child’s tears, or to serve, quickly converted, as a coin purse or as a sweet love token.

Will I become some strange old woman who collects handkerchiefs?

Comments